Author Archives: Leo

“The Invincibles” Arsenal 2003-04 Analysis (3) – Henry-Bergkamp Partnership

What is the traditional 4-4-2 forward pair partnership? Marziali and Mora (1997) had an argument about that in the book “Coaching the 4-4-2”. They argued that one player play as “target man” who is physically strong and good at heading. Also, he is able to play with the opposing goal at his back. The other player is rapid, quick with good individual skill, who likes starting from a distance and moving all over the attacking front. As the forward pair in the invincible team, I argued Henry-Bergkamp partnership was one of the best in Premier League history but it was not a traditional 4-4-2 forward pair partnership because of their 3 features:

Feature 1: Separation of Duties

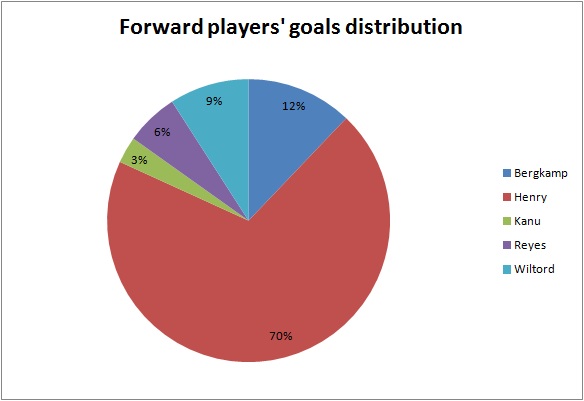

Henry was the focal point of attack and Bergkamp had supporting role. This is supported by two evidences. Firstly, Henry scored 70% of forward players’ goal (exclude penalty) as shown in the following chart. However, it must be clarified that Arsenal was not a one-man team.

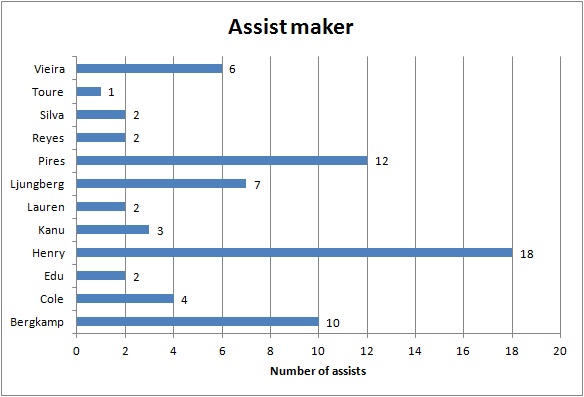

Secondly, in terms of building up goals, Bergkamp was a more efficient player than Henry which I explained last week. On the other hand, they both contributed well in terms of assist.

They were in the top 3 players in making assist. This forward partnership was so important in the team because they made 41% of team assists. If we consider the efficiency of making assist, their contribution is more obvious.

They were the top 2 most efficient assist makers in the team and Pires dropped to third. In short, Henry focused on scoring goals and making assists. Bergkamp focused on involvement of build-up of goals and making assists.

Feature 2: Different playing areas on the field

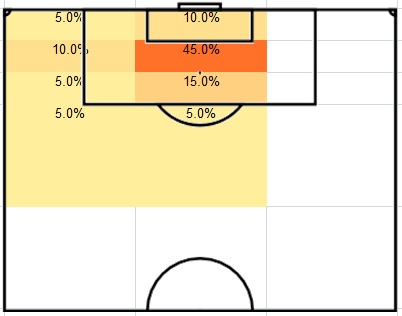

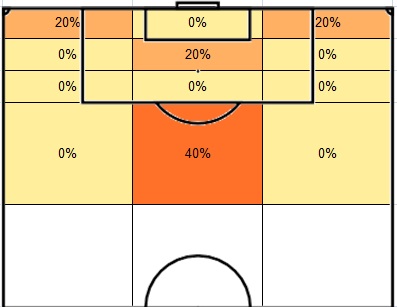

Henry played mostly at left flank and moved to central area to score goals. This argument was supported by two evidences by analysing where he scored goals and where he made assists. By considering open play goals, Henry scored 75% in central area (most inside penalty box) and 25% at left flank as shown in the following diagram.

This evidence is not strong enough so we have to analyse where he made assists as well to see where he played mostly.

Two results can be taken from this diagram. Firstly, Henry played mostly at left flank as he made 55.6% of assists on the left side comparing with 38.9% on the central area and 5.6% on the right side. Secondly, if we focus on the left side, you will realise most of his assists were made in the final 18-yard of left side (44.4% of total) while he only made 11.2% assists outside the penalty area on left side. The reason of it will be explained later in this post. Therefore, we can conclude that Henry played mostly at left flank and then drifted to centre of penalty area to score goals.

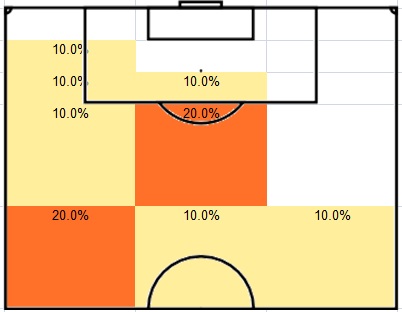

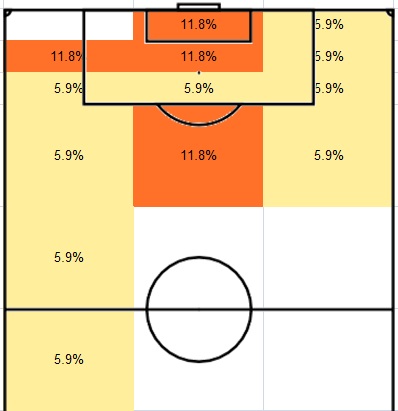

On the other hand, Bergkamp played more centrally than Henry and mostly spent his time outside the penalty area to provide support to teammates. As shown in the following diagram, Bergkamp made 70% of his assists outside the penalty area. His percentage of assists in central area and right side was more than that of Henry.

A comparative analysis could be made by making a table about where they made assists which shows their different playing areas.

| Henry | Bergkamp | |

| Final 18-yard area | 66.7% | 30% |

| Outside 18-yard area | 33.3% | 70% |

It supports my arguments above that Henry focused on playing left and scored in central penalty area while Bergkamp played more centrally and stayed outside penalty area in most of the time to provide support.

This is a video example showing their position. Even they both started on the left side, when the ball was moved to right side, Bergkamp tended to move to centre and Henry stayed at left flank until he moved to centre to score the goal in the penalty area.

Feature 3: Playing styles fit in each other

Henry was strong at attacking space behind the defence. This could be analysed by looking at the assists styles of Henry’s goals. Note that the goals from penalty and direct free kick were excluded.

Three characteristics of Henry could be seen in this chart. Firstly, Henry was a striker who didn’t rely on crossing assist (15%). In a traditional 4-4-2 system, the strikers rely on the crossing from two wingers/wide midfielders but it was not the case in the invincible team. Secondly, he was good at exploiting space behind the defence because the largest proportion of his goals (30%) was come from through ball. It fits his styles as he was a fast runner. Thirdly, technically he was good because he could score goals by dribbling past his opponent (15%) and by receiving passes to his feet (20%).

Even both players contributed well in terms of number and efficiency of making assist, their assist styles were different. This is supported by two evidences. Firstly, Henry was strong at crossing.

33% of his assists were made by crossing. It can explain why 44.4% of his total assists were made in the final 18-yard area on the left side which is mentioned above. If you consider two evidences, 66.7% of his assists were made in final 18-yard area and 55.6% of his assists were on the left side, the final 18-yard area on the left side is the overlapped area which was Henry’s key playing area.

Bergkamp was strong at providing through ball (penetrative pass to the back of defence).

The result of Bergkamp’s assist styles is more obvious than that of Henry. 40% of his assists by made by through ball. It fits the previous finding that Bergkamp tended to play outside the penalty area providing support.

The different playing styles of these two players brought out two main benefits. Firstly, they provided variety of assist styles to benefit the team based on their strengths. Secondly, Bergkamp’s assists style (through ball) fits Henry’s goal scoring style (attacking space behind the defence) perfectly. This is shown in the following video example:

In conclusion, I would like to use a table to summarise my analysis.

|

Henry |

Bergkamp |

|

| Separation of duties | Goal scoring + making assist | Build-up of goals + making assist |

| Playing areas | Left flank + final 18-yard area | More central + Outside penalty box |

| Playing styles | Attacking space behind defence + crossing | Playing through ball |

Their partnership was not a traditional 4-4-2 forward pair partnership. I argued that it was still an excellent partnership in Premier League’s history because they fitted in each other based on their strengths.

Reference:

MARZIALI, F. and V. MORA, 1997. Coaching the 4-4-2. Spring City: Reedswain

“The Invincibles” Arsenal 2003-04 Analysis (2) – Were Arsenal a one-man team?

No doubt, Henry was the most important player in “the invincible” squad. However, were Arsenal a one-man team in 2003/04 season? This question would be analysed in this post. As the top goal scorer in the team, Henry scored 41% (30) of the team goals (73) in that season.

As shown in the above chart, Henry absolutely outperformed other players in terms of goals. Apart from Henry and Pires, nobody else scored more than 4 goals. Probably the best striker in the world at that time, Henry was able to do something different comparing with other strikers. For example, a target man needs crosses provided by teammates. A poacher needs through ball or penetrative pass. However, when somebody gave Henry the ball, he had the ability to do the rest by himself. For example, the following video shows how good his dribbling was.

In this goal, the assist was made by Henry as well because I will code it as “self-assist” if the goal scorer scored the goal by beating opponents by dribbling. My definition of “one-man team” is that the team is heavily (or just) relying on the performance of certain player. Was that the case in the “invincible” squad? The above evidences and examples may suggest a “yes” but I argue Arsenal were NOT a one-man team because of three reasons.

Reason 1: Pires was an efficient and reliable goal scorer also

There were seven penalty goals which were all scored by Henry, so it would be fair to take them out and look at the goal distribution again.

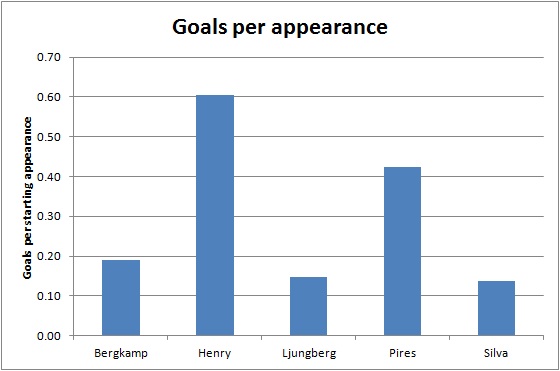

Henry’s 23 goals took 35% of the team goals. As shown in the chart, there was a second reliable goal scorer in the team as well. Pires scored 14 goals which were 21% of the team goals. Apart from analysing the number of goals, the efficiency should be considered as well. The top 5 goal scorers in the team were taken out. Their number of goals were normalised by considering their number of starting appearance as well.

Henry was still the most efficient striker, scoring 0.61 goals per appearance. The goal scoring efficiency of Henry and Pires were much better than the rest of the team. The above two charts show that in terms of goal scoring, Arsenal were not only relying on Henry due to the presence of Pires who was a efficient and reliable goal scorer as well. When the position of the goal scorer was considered (own goals were taken out), it further supports my argument.

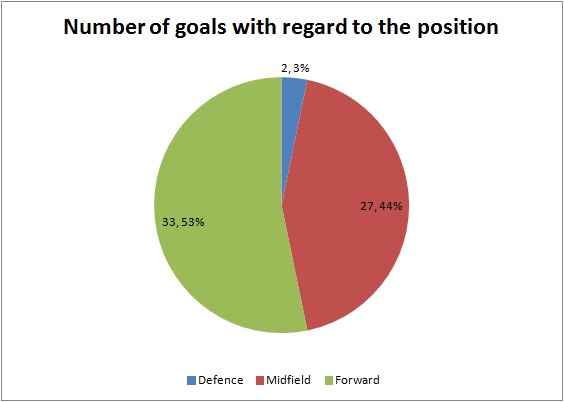

The forward players scored the most (33 goals) which was 53% of the team goals. However, it also shows that the midfield of Arsenal was a strong goal scoring force by scoring 44% of the team goals. I agreed that the forward players heavily relied on Henry who scored 23 out of 33 (70%) forward players’ goals. However, it was not the case for the whole team.

Reason 2: The responsibility of making assist were shared by several players

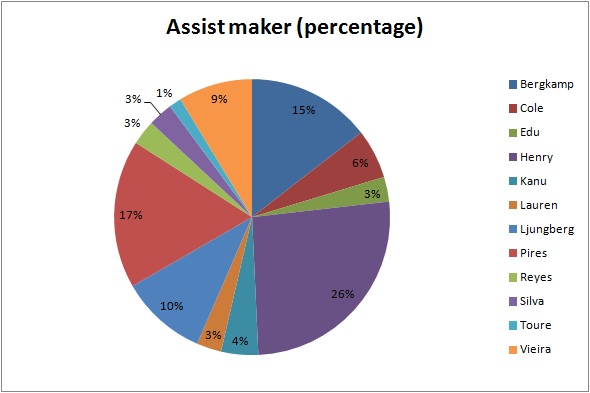

Apart from being the top goal scorer of the team, Henry was also the top assist maker as well, making 18 assists in that season. Only 3 of them were self-assist by dribbling past opponents before he scored. However, Henry’s effect was not as obvious as shown in the goal chart because he took only 26% of the team assists.

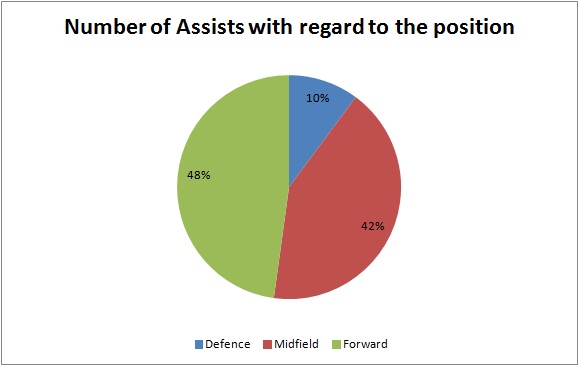

The chart shows that the responsibility of making assist was well shared by several players. The most obvious top 3 assist makers were Henry (26% – 18 assists), Pires (17% – 12 assists) and Bergkamp (15% – 10 assists). This chart could be analysed in two perspectives. Firstly, Arsenal had a good strikers’ partnership of making assist. Although Bergkamp hadn’t scored many goals (4), his contribution in making assist was obvious. The Henry-Bergkamp partnership took 41% of the team assists. Secondly, the 6th assist maker was Cole who was a left back. Considering the left side combination (left back, left midfielder, left forward), the Cole-Pires-Henry combination took 49% of the team assists. That means for every two goals Arsenal scored, one of them was assisted by one of the left trio. It shows how strong the left side of Arsenal was (I will write a post for this topic in future). The above two evidences show that even Henry was a world-class player, there were some top players playing with Henry at that time. By considering the position chart, it shows that the effect of forward players in making assist was not as strong as goal scoring, decreasing from 53% to 48%.

The contribution of defenders increased a lot from 3% in goal scoring to 10% in assist making, while midfielders had a more or less same percentage (44% and 42%).

Reason 3: Henry was NOT the most efficient player in building up goals

Looking at the assist can only give a clue about the final pass; it doesn’t show you the build-up of the goal. In order to analyse the players’ contribution in the build-up of the goals, the players involved in the goals have to be considered. Note that the set play goals were excluded in the following charts.

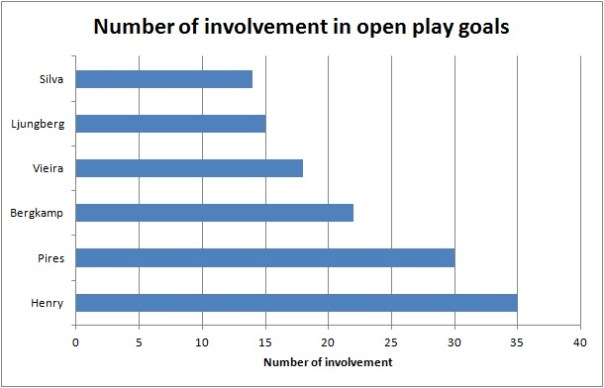

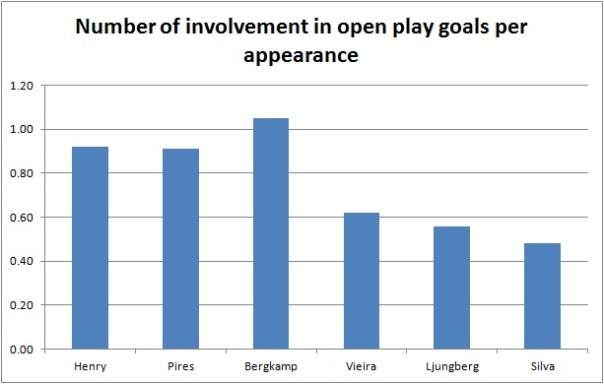

Only the top 6 players were shown in this chart. In 52 open play goals, Henry was involved in 35 of them (67.3%). There is a little gap between the top 2 players (Henry – 35, Pires – 30) and the other players. It shows that Henry and Pires were still the two key players in Arsenal’s build-up of goals. Similar to the assist chart, Bergkamp got the 3rd position. However, in the starting line-up of Arsenal, Bergkamp had the least starting appearance (21) comparing with Henry (38) and Pires (33). It shows another picture when the appearance was considered to normalise the data.

In fact, the overall trends of two charts are very similar but Bergkamp’s performance and efficiency was the best when the data were normalised with number of appearance. For every single starting appearance, Bergkamp was involved in building up at least 1 goal. On the other hand, the difference between Henry and Pires became much less (only 0.01) which imply that their efficiency were pretty much the same. With the age of 34 in that season, Bergkamp didn’t play as much as before and wasn’t the focal point of attacking. However, with his high level of technique and vision, he still played a key role in building up the goal even he was not the person to make the assist every time. The following video is an example to show Bergkamp’s vision and technique to pass a “killer ball” penetrating two lines of defence.

To conclude, there is no doubt that Henry was a key player in the “invincible” squad. However, Arsenal were not a one-man team because other players played key roles in different aspects. Pires provided efficient and reliable source of goals. Cole had a great contribution of making assist. Moreover, Cole played a key role in assisting Pires and Henry in the left side because the combination of these three players took half of the team assists. Although Bergkamp didn’t contribute much in scoring goals, his contribution was mainly focused on assist and build-up of goals. He was the most efficient player in building up goals.

“The Invincibles” Arsenal 2003-04 Analysis (1) – Squad and formation

Arsenal 2003/04 unbeaten title-winning team have been voted as the Best Team in the Premier League’s 20 seasons awards. It is the first team to win the Premier League title having not lost a game. The last team to achieve it was over a hundred years ago. It was a big achievement that earned the nickname “The Invincibles”. Therefore, it is worthy to analyse this team to see what we can learn. How did they play? What were the characteristics of the players? It may not have the best players in every position but the chemistry they formed was the best at that time. I am trying to find it out through analysing the 38 league games.

Arsene Wenger used 22 players in the whole season. However, Justin Hoyte and David Bentley had only made 1 appearance, comparing with the rest of the team making at least 9 appearances (more than 20% of the 38 games). Therefore, it is reasonable to exclude these two players and focus on how Wenger used those 20 players in the whole season. This was the first team line up:

Goalkeeper Jens Lehmann played every league game in the whole season.

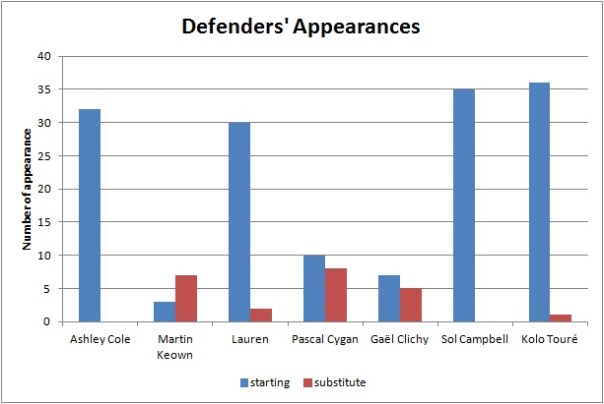

Defenders:

The above chart clearly shows that Cole, Lauren, Campbell and Toure were the first team players of the back four. Keown had more substitute appearances (7) than starting appearances (3); especially four of them were in the last four games after Arsenal had won the title on 25/4/2004. Therefore, Cygan was the first choice back up in the centre back position. On the other hand, Clichy was the back up of Cole in left back position. Who was the back up of Lauren in right back position? Wenger used a different approach. Instead of putting a right back player as the backup of Lauren, Wenger used the versatile Toure wisely. The following diagram shows Wenger’s approach about the backup of right back. When Lauren was not available, Wenger moved Toure to the right back and let Cygan played as centre back:

Even Toure moved from a centre back to a right back, he was more than a defensive right back. His speed and strength made him playing well as an attacking right back also. The following video is an example.

Even Toure moved from a centre back to a right back, he was more than a defensive right back. His speed and strength made him playing well as an attacking right back also. The following video is an example.

In short, the versatility of Toure gave the consistency in Arsenal’s defence, letting Wenger used 6 players mainly throughout the season.

Midfielders:

The chart of midfielders is not as obvious as that of defenders. It shows that more rotation was happened in midfielders. However, it still shows that Vieira, Pires, Ljungberg and Silva were the first team midfielders. Edu shouldn’t be ignored because he was Wenger’s first choice substitute in midfield, having 16 substitute appearances. In fact, if total appearances were considered, Edu had 29 (13+16) which is the same as Vieira.

Only 6 midfielders were mainly used in the whole season showed the versatility of these players, especially the two backup players Parlour and Edu who played as both central and wide midfielders. Moreover, Pires and Ljungberg were able to play at both flanks. The combination of these 6 players gave the flexibility and consistency of a solid Arsenal midfield.

When Ljungberg was not available, Parlour was the first choice of Wenger to replace the right winger role:

When these two players were not available, Pires played as a right winger as Edu played as a left winger:

It happened 4 times during the season. However, Wenger used a different approach in the late second half of the season, keeping Pires as left winger and put Wiltord or Reyes as the right winger.

When Pires was not available, Wenger moved Ljungberg to the left and played Parlour as the right winger:

If both Pires and Ljungberg were not available, Edu could play as a left winger also.

The rotation in central midfield was simple. Parlour and Edu were the backup of Vieira and Silva. However, the interesting point is that even Edu was the first choice substitute in Wenger’s mind; Parlour was the primary backup central midfielder when either Vieira or Silva was unavailable. There were 18 games when one of them was unavailable, Parlour started 11 of them and Edu started only 7 of them.

The appearances and rotation in midfield could be linked to the analysis of formation. In 4-4-2, the central midfielder substitutes were still able to cover the wide position as wide midfielder or winger (e.g. Parlour in right flank, Edu in left flank). It is because the two strikers playing upfront are the main goal scoring power. The substitutes could act as a supporting role in wide position even though they are not good at attacking. Comparing with the 4-3-3, 4-5-1 or 4-2-3-1 nowadays, it is rarely to see a central midfielder to take over the winger position because the winger position in these formations requires more attacking attributes due to the lone striker system.

Strikers:

Henry was definitely a first team member starting all 38 league games. Therefore, what Wenger had to decide is using whom as Henry’s partner. Wiltord got more chances firstly. In the first 10 games, he started 5 times and played 3 times as substitute. However, he was not in Wenger’s first team plan since then. Bergkamp, having 21 starting appearance, was the partner of Henry in most of the season. However, may be because of Bergkamp’s age, he didn’t play many games continuously. Wenger used Kanu, Aliadiere and Wiltord as the backup. The situation changed after January’s transfer window. Reyes joined the team and got the chances immediately. The total number of games Reyes played in half season (13) was more than Wiltord (11), Kanu (10) and Aliadiere (9) playing in the whole season. Note that in some exceptional cases, Wenger used Reyes and Wiltord as left and right wingers.

For further analysis of Arsenal invincibles squad, please go to the links below:

Part 2 – Were Arsenal a one-man team?

Analysis of top 4 strikers in League 2 (2)

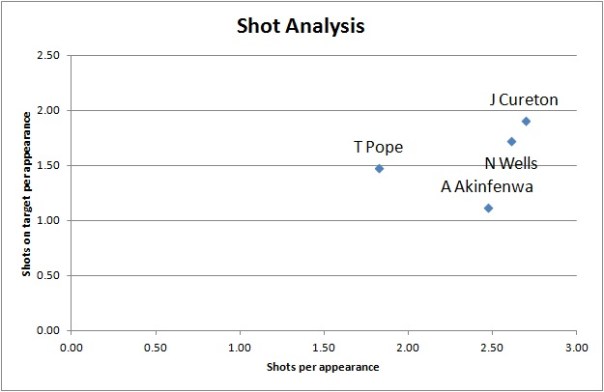

The analysis is continued following the first part last week (here). In the shot analysis, when treating unequal frequencies of starting appearances, the data are “normalised” by dividing the data by the frequency of starting appearances.

Although the other three strikers have at least 2.5 shots per appearance, T Pope had only 1.83 shots per appearance which is significantly lower than others. In terms of getting shot chances, T Pope is weaker than the other three strikers. On the other hand, A Akinfenwa showed his weakness as he only got 1.12 shots on target per appearance. N Wells and J Cureton are similar, both getting high number in shots and shots on target. Even T Pope got less chance to shoot; he still managed to get 1.48 shots on target which means he utilise the chances well. If you look at this chart only, you may wonder why T Pope is the leading goal scorer in League 2. It is all because he is particularly strong at catching the chances even the chances he get are less than others. This brings us to the next analysis chart: Accuracy rate vs Conversion rate.

Accuracy rate = no. of shots on target / no. of shots total

Conversion rate = no. of goals / no. of shots total

T Pope is outperforming others in this chart in both rates. In previous chart, N Wells and J Cureton showed they got more chances to shoot and they did well in number of shots on target. It is reflected in their decent accuracy rate (66% and 71%). However, conversion rate is their weakness (26%) and it explains why they can’t be the leading goal scorer even they got more chances. T Pope’s conversion rate (48%) is 22% more than them. A Akinfenwa did well in conversion rate (31%) but he is weak at accuracy rate (45%). From the above two charts, you may realise N Wells and J Cureton are so similar. They both good at getting shooting chance, have a decent accuracy rate but weak at converting chances into goals. T Pope is another type of striker who is highly efficient. A Akinfenwa strike a balance between both types.

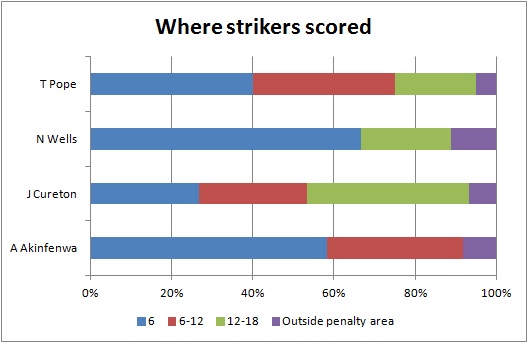

In analysing where the strikers scored, we can find out other characteristics of the strikers. A Akinfenwa is weak at long shot because only 8% of his goals were scored outside 12 yards from the goal line. It is reasonable if we combine the finding last week suggesting that he is strong at scoring by headers and in set play. N Wells is strong at scoring in 6-yard box (67%). Last week, we found out that he hasn’t scored any goal by header. If we combine both together, I guess that his goal scoring style is like “poacher” to catch the chances in 6-yard box by using his agility rather than strength. T Pope and J Cureton had a good balance in goal scoring area with T Pope stronger at 6-yard box and J Cureton stronger at 12-18 yard area.

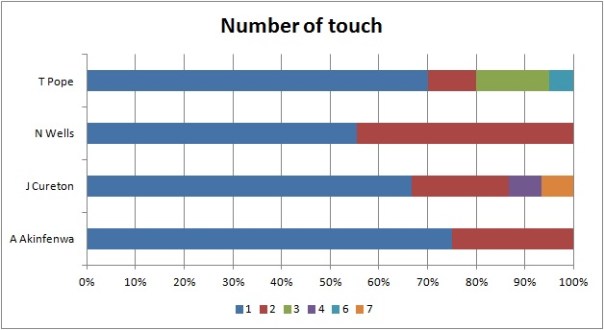

This chart fits our finding beforehand. A Akinfenwa is strong at heading and he scored 92% of his goals within 12-yard area from goal. It is reasonable to see that he scored all goals by using 2 touches or less. N Wells fits his “poacher” style by scoring all his goals using 2 touches or less. In terms of using 3 touches or more, T Pope had the highest percentage (20%). If we combine our finding of his high conversion and accuracy rate, it can somehow show his composure in front of the goal by getting the best chance to score.

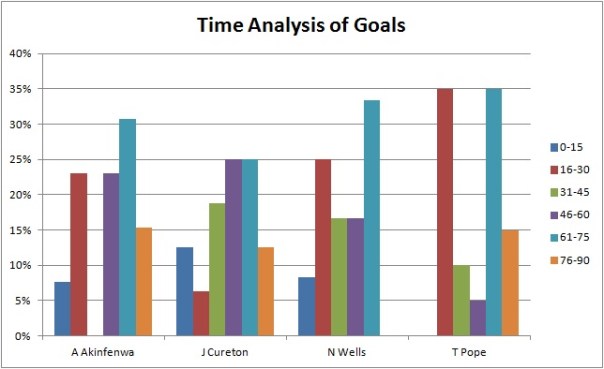

We can find out the strikers’ particular goal scoring pattern by using time analysis. Firstly, A Akinfenwa is much stronger in second half, only 31% of his goals were scored in the first half. Note that 46% of his goals were scored in the last 30 minutes of the game. This may be explained by his strength and strong header to attack at the end of the game. N Wells haven’t scored any goal in the last 15 minutes of the game. It is reasonable if we sum up the previous findings. Usually there will be direct style and long ball in the last 10-15 minutes if a team is losing, but N Wells is not the same type of striker like A Akinfenwa. N Wells is strong at feet and agility rather than header and strength. T Pope’s goal scoring pattern is interesting. 70% of his goals were scored in the mid 15 minutes of the halves. Only 5% of goals were scored in the first 15 minutes of the halves. He may need time to “warm up” in the game before showing his goal scoring power. Then we move on to the assist analysis to see how the strikers’ goals were assisted.

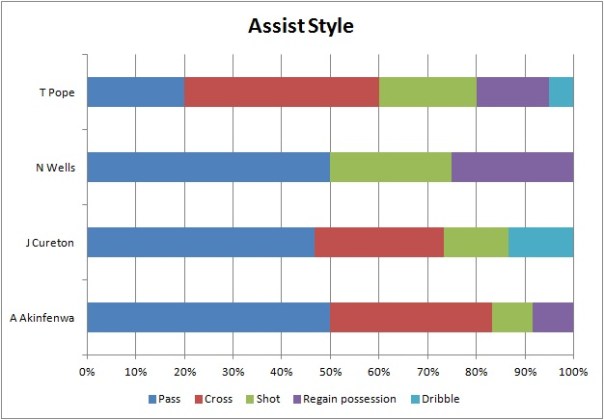

J Cureton is stronger than others in dribbling which can create the scoring chance himself. A Akinfenwa and N Wells have no dribbling goals, that means they heavily rely on the support from teammates because they can’t create chances themselves. It is reasonable if we refer back to the characteristics of these two strikers. N Wells is strong at scoring in rebounds because 25% of his goals were assisted by teammates’ shots. It fits his “poacher” style mentioned above. Moreover, none of his goals were come from crossing. Surprisingly, only 20% of T Pope’s goals were assisted by passing. He relied on crossing (40%) more than other strikers. Then we analysed where the assists were. Please note that only open play goals assists were shown in the following diagrams.

A Akinfenwa:

As I mentioned last week, A Akinfenwa is strong at headers and set play. This diagram shows that his headers goals were heavily linked to set play. Therefore, only 40% of open play goals assists were from the flanks.

J Cureton:

J Cureton’s goals were mainly assisted from the right flank and centre. If any team play against Exeter, they should pay more attention to defending at their left flank (particularly from 12 yard to outside the penalty area) because 35.7% of J Cureton’s goals were assisted from these two zones.

N Wells:

This diagram further supports my previous arguments about the characteristics of N Wells. He is strong at agility and feet, weak at headers and strength. He plays like a “poacher” but none of his goals were come from crossing. Therefore, this diagram is under expectation that 83.3% of assists came from centre. By using this diagram, we know more about how he scored. 33.3% of assisted were from 12-18 yard area. If we combine this with the previous findings:

- 67% of his goals were scored in 6-yard box

- 50% of assists were passing, 25% of assists were shots

- 89% of goals were scored by feet

- 100% of goals were scored by 2 touches or less

We can figure out a full picture how he scored open play goals: his teammates attack through middle of the pitch, making a pass or take a shot (particularly 12-18 yard area). If it is a pass, he would at most take one touch before the shot. If it is a shot, he would take the rebounding chance in the 6-yard box.

T Pope:

From last week’s finding, T Pope is an all-round striker. He is good at scoring by right foot, left foot and header as well. Even in this assist diagram, the assists covered a wide range of areas. These make defending the leading goal scorer a difficult task. However, it is still a useful tip to find out that 41.3% of assists came from centre.

I think the whole analysis process covers enough details to find out the characteristics of the strikers. This is the end of the striker analysis. I may make a review about striker analysis at the end of the season.

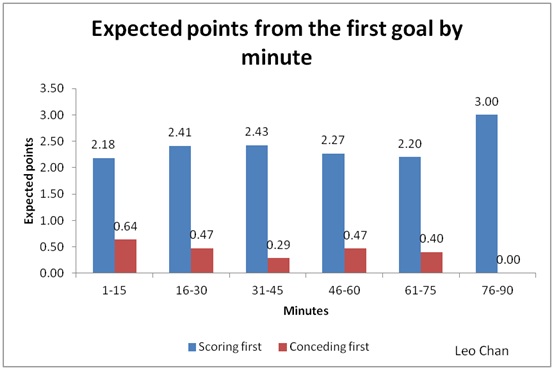

Analysis of top 4 strikers in League 2 (1)

Different strikers have their own characteristics in scoring goals. They can somehow reflect their teams’ goal scoring characteristics as well. We will focus on the top 4 goal scorers in League 2. The analysis is quite long so I divide it into two posts. The second part will be continued next week. The following table shows who they are, their team and the position in league table. Please note that all the data is updated to 28/12/2012.

|

Name |

No. of goals |

Team |

Team league position |

|

T Pope |

20 |

Port Vale |

2nd |

|

J Cureton |

16 |

Exeter |

10th |

|

A Akinfenwa |

13 |

Northampton |

11th |

|

N Wells |

12 |

Bradford |

5th |

It seems that being a top team does not necessarily need a top goal scorer as only 2 of the top 4 strikers are playing for a team in the top 7 of the table which is the promotion playoff line. The other 2 strikers are playing for the teams in the mid-table position. However, I agree that a high quality striker can bring an average team into a top team.

Although T Pope is the top goal scorer, he doesn’t have the highest percentage of team goals. J Cureton is the striker whom the team relies on the most because he scored 47% of the team goals. It is worthy to note that all 4 strikers scored more than one-third of the team goals.

Apart from looking at the number of goals, we should analyse by looking at the starting appearance as well in order to understand the efficiency of the strikers.

As the top league goal scorer, T Pope is the most efficient striker as well. He scored 0.87 goals per starting appearance. Note that J Cureton scored more goals than A Akinfenwa but A Akinfenwa is more efficient because he scored slight more goals than J Cureton in terms of goals per starting appearance.

We discussed how important the first goal before (here) so it is worthy to analyse the strikers’ ability to scored the first goal in the match.

A Akinfenwa performed much better than other strikers in terms of first goal. 46% of his goals were first goal, which is obviously higher than that of T Pope (30%) and J Cureton (31%). His percentage of first goal is almost double the percentage of N Wells (25%). This is A Akinfenwa’s strength and people may ignore it if we don’t analyse the strikers from this perspective.

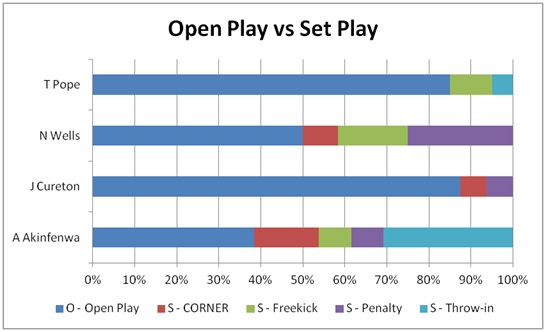

Then we move on to analyse the relationship between open play and set play goals.

T Pope (85%) and J Cureton (88%) scored most of their goals in open play, obviously higher than the percentage of other two strikers. N Wells struck a balance by scoring 50% open play goals. However, 25% of his goals were come from penalties. A Akinfenwa is particularly strong at scoring set play goals as 62% of his goals were from set play. Note than 31% of his goals were from throw-in which is much higher than other strikers. Moreover, he scored the highest percentage of goals in corner (15%) as well. He is a good example showing that the team top goal scorer can reflect the goal scoring characteristic of the team. Northampton scored more goals in set play (53%) than open play (47%). In all 18 set play goals, 50% of them were came from throw-in. The goal scoring pattern of Northampton and A Akinfenwa is almost the same even he scored only 35% of team goals.

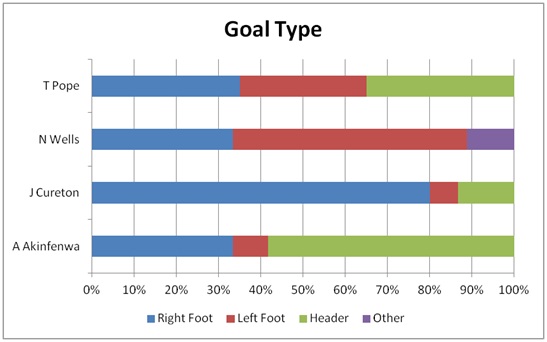

Then we will analyse how the strikers scored the goals.

Note that I have excluded the goals from penalty in this chart. T Pope shows he is an all-round striker and this may explain why he is leading goal scoring table. The goals he scored by using his right foot (35%), left foot (30%) and head (35%) were almost evenly distributed. J Cureton is particularly strong at scoring goals by right foot (80%). However, it can be treated as a weakness as well because it is easier for the defender to mark him. N Wells is weak at header as he hasn’t scored any goal by header. However, he is strong at scoring goals by using both feet. A Akinfenwa is strong in air as he scored 58% of his goals by head. It fits what we find that he scored the highest percentage of goals from set play (62%) among 4 strikers, particularly in throw-in (31%) and corner (15%). In short, scoring goals by header in set play is the strongest weapon of A Akinfenwa.

The analysis will be continued next week by analysing these 4 strikers from different perspectives including where they scored, when they scored, where assist came from, assist types, shots total and shots on target.

League 2 result analysis: how hard to hold the leads?

If a team scored the first goal in the first half and hold it until the end of first half, what does that mean? How big is the chance to win that game? Or is there any chance for the opposition team to win it back? How big is that chance? What are the differences in holding 1 goal and 2 goal differences in terms of the percentage of chance to win the game finally? Are 2 goal differences safe enough to win a game? The follow analysis will answer all the questions above by analysing the league 2 result this season (updated to 20/12/2012).

I have compared the half time results with full time results and built a connection between half time leads and full time results by using the goal difference.

When the game was tied at half, there was a 42% chance to have a draw at the end of the game. In other words, there was a 29% chance that one of the two teams won the game finally.

When the game was tied at half, there was a 42% chance to have a draw at the end of the game. In other words, there was a 29% chance that one of the two teams won the game finally.

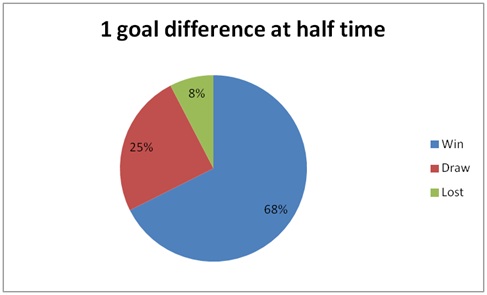

However, if a team is leading by 1 goal at half time, the chance of winning the game increased significantly from 29% to 68% which is a pretty high chance. It is worthy to note that it still had a 8% chance to lose the game even the team had a 1-goal lead at half time. That’s why so many people claimed that the team need a “two-goal cushion” to get the three points. Is “two-goal cushion” a three-point guarantee in league 2? We are going to find out.

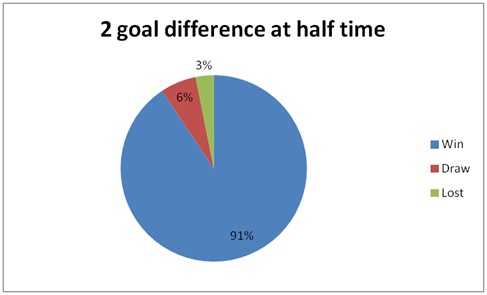

When a team was leading by 2 goals at half time, the chance of winning the game increased from 68% to 91%. In other words, it was not a 100% guarantee yet because 6% of teams managed to get a draw finally. Surprisingly, there was still a 3% chance that the leading team eventually lost the game. In short, there was 1 out of 10 chances that the leading team can’t get the three points at the end of the game. The “two-goal cushion” may not be as safe as people thought in League 2.

However, once a team was leading 3 goals at half time, the match is over. No team could manage to get a draw or win it back if they are losing at a 3-goal margin at half time.

Similarly, there were two occasions that a team was leading 4 goals at half time and they all won it eventually.

To summarise, going from a tie to a lead by 1 goal, 2 goals and then 3 goals or more, the chance of winning the game increased from 29% to 68% to 91% and then to 100% eventually. “Three-goal cushion” was a guarantee of the three points instead of two-goal.

In terms of analysis, this analysis could go further in depth by separating the home and away game results to see whether it is easier to hold the lead in home.

Time Analysis of League 2 teams

There are 690 league 2 goals (updated to 13/12/2012). There are many perspectives of analysis of goal scoring. This article will focus on the time at which goals are scored during match play. The analysis would be useful for coaches because the relationship between goal scoring and time would appear to be linked to physical conditioning and characteristics of different teams.

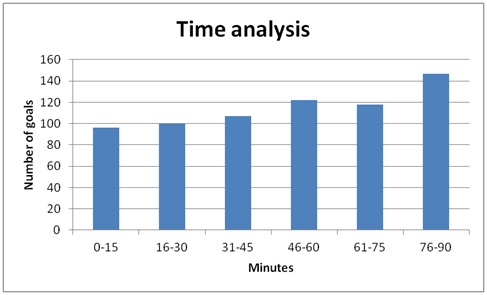

I divided the 90 minutes into six 15-min periods. The following chart shows that there is a systematic and significant upward trend in the number of goals scored as time progressed. This is a support to previous research suggesting an increase in the frequency of goals scored as a match progresses (Jinshan et al., 1993; Reilly, 1996).

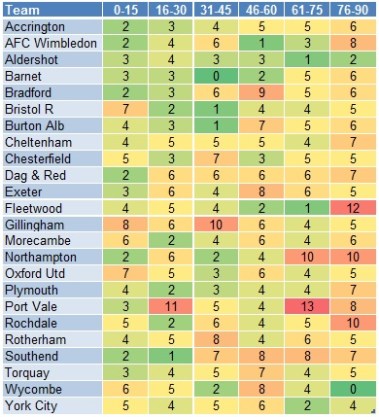

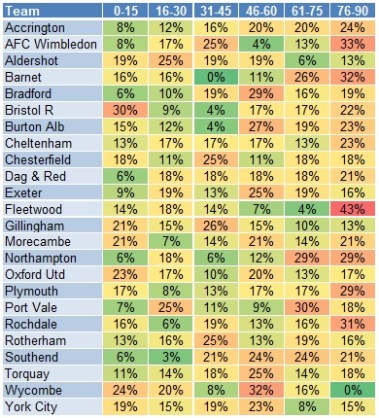

Then we move on from the genearl perspective to the team perspective to analyse the goals. The following table shows the number of goals scored in six periods of different teams. The data were shown in a Red-Yellow-Green colour scale. That means, the higher number would be highlighted by red and the lower number would be highlighted by green for better visualisation of the data.

Generally, most of the teams scored more goals in the second half which fit the general trend. However, Aldershot is an exception as they scored the least goals in the last 30-min period among League 2. On the other hand, Fleetwood is expertised in scoring late goal in the last 15-min period. The 12 goals they scored is remarkably higher than the goals they scored in other periods. Northampton and Port Vale are strong in the last 30-min period as well.

However, if we just count the goals scored, it is not showing the whole picture of analysis because stronger teams scored more goals. If we want to find the characteristics of the teams, we have to convert these data into percentage. For example, in the first 15-min of the game, Bristol Rovers scored 7 goals, same as Oxford United but less than Gillingham. A different table will show you a different picture. The following table shows the same set of data in percentage form.

Bristol Rovers become the best team to score early goals which is obviously a characteristic of this team. Even Gillingham scored the most goals in this period, it is only 21% of their total number of goals. This percentage is less than Oxford United and Wycombe.

The result of Fleetwood becomes more obvious. It seems that they tried to save energy in the 46-75 minutes by scoring only 11% of goals and then dominate the final 15 minutes in scoring 43% of their total goals.

Wycombe shows the same trend in both halves that they scored most of their goals in the first 30 minutes. They are particularly weak in the last 15 minutes of the half. The possible explanation is the deterioration in physical condition of players is more serious in Wycombe. Accrington, Bradford and Southend have a similar characteristic because they all scored less than 20% of their goals in the first 30 minutes of the game. It would be a good strategy to start attacking early when other teams play against these three teams.

Reference

Jinshan et al., 1993. Analysis of the goals in the 14th World Cup. In: J. C. a. A. S. T. Reilly, ed. Science and Football II. London: E. and F.N. Spon, pp. 203-205.

Reilly, T., 1996. Motion analysis and physiological demands. In: T. Reilly, ed. Science and Soccer. London: E. and F.N.Spon, pp. 65-81.

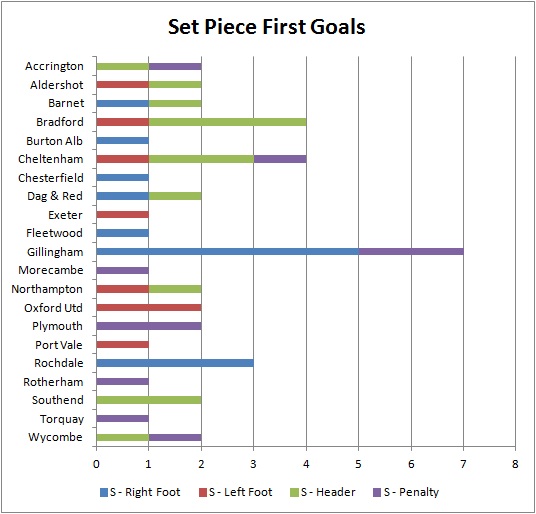

England League 2: How important is the first goal?

Performance analysis is usually thought as an elite tool which is for big clubs and high level leagues only because big clubs have the resources to afford analysis software and different IT technological support. In my opinion, it should not be the case. Performance analysis is a process which can be done by small football clubs also. Small clubs don’t have the big budget to do as much as the big clubs do but we are going through the same process. That’s why I would like to share my experience and work of doing performance analysis in a League 2 club.

No doubt, everybody knows the first goal is important. However, do they know how important it is? How to transfer the concept of “importance” to a quantified stuff, such as points? Different leagues have different levels; we can’t apply all the findings in Premier League to League 2 as there are so many differences such as playing styles, distance covered, etc. I would quantify the concept of “importance” by making statistics about the points got at the end of the game by a team when they scored or conceded the first goal. I would call it as “expected points” which means the points a team expected to get from the first goal. I would use different perspectives to analyse the first goal in league 2:

- Time of goal

- Match location (Home or Away)

- League position (In groups)

- Team

Average

I used the first 8 league games in each team, which means 95 games in total (the game between Wycombe and Bristol Rovers on 25/8 was excluded as it was abandoned 66 minutes). Among these 95 games, 86 games had goal(s). The following chart shows that the expected points of scoring first and conceding first are 2.30 and 0.49 in average. These would be used as a reference for other results found by using different perspectives.

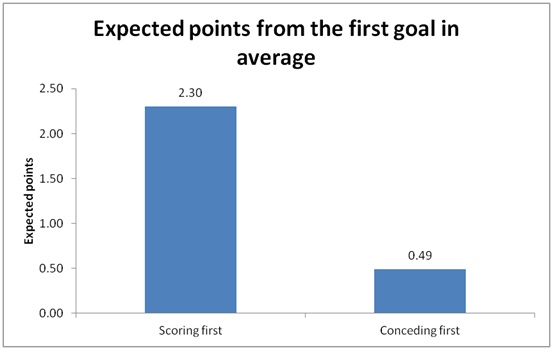

Time of Goal

Time is an important factor of first goal. I divide 90 minutes into 6 categories, which mean 15 minutes per category.

Teams got most expected points (3 points) when they scored the first goal in 76-90 minutes. It is reasonable as there is not much time for the opponent to fight back. However, there were only 2 goals scored in this timeslot which makes this finding not so persuasive since the sample size is not big enough. I’d rather to ignore this timeslot. Teams could get high expected points if they score the first goal between 16 to 45 minutes, 30 minutes timeslot before the interval. Since the expected points drops after 45 minutes, the first goal scored within 30 minutes before half time are more valuable than first goal scored 30 minutes after half time. I heard argument that scoring before the interval is a great advantage but statistics in this chart showing that the expected points from 16-30 minutes and 31-45 minutes are similar. However, a similar argument may be right. Scoring before the interval is particularly damaging to the opposition. As you can see from the chart, teams conceding first goal just before half time could only get 0.29 expected points which is obviously less than conceding first goal in other timeslots which fits the argument. Nobody would like to concede an early goal but statistics show that the team don’t have to be pessimistic even they do concede an early goal within 1-15 minutes. Teams can get 0.64 expected points which is the highest comparing with other timeslots. This can be explained that the team still have much time to bounce back.

Location

From the above chart, teams scoring the first goal in home were more likely to keep the winning positions and get more points than scoring first in away game. It may be explained by home advantage that teams play better in home. However, the same argument can’t be applied in conceding first because they both got 0.49 expected points. Home advantage may help the team more to keep winning position but not bouncing back from behind.

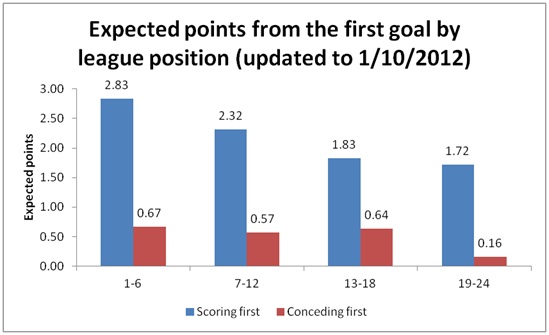

League Position

Note that the league positions are updated to 1/10. In scoring first (blue columns), an obvious downward trend can be seen which shows that stronger teams were more likely to retain their winning position when scoring first. There is a big gap difference (0.51 expected points) between positions 1-6 and positions 7-12. Another big gap difference (0.49 expected points) appears in between positions 7-12 and positions 13-18. However, there is not much difference (0.11 expected points) between positions 13-18 and positions 19-24. I would say in terms of the ability to retain winning position after scoring first, there are 3 levels in league 2. Positions 13-24 would be at more or less the same level. Positions 7-12 are much better than the bottom half of the table but positions 1-6 are much better than positions 7-12 as well.

The downward trend can’t be seen in considering the conceding first (red columns). Positions 13-18 got a better result than positions 7-12, similar to positions 1-6. In fact, it surprises me a little bit as I expected the downward trend in conceding first same as scoring first. We would look at individual teams afterwards to see what we can find. However, the expected points from positions 19-24 (0.16 points) are obviously less than other groups. It shows that they struggle to bounce back if they concede the first goal.

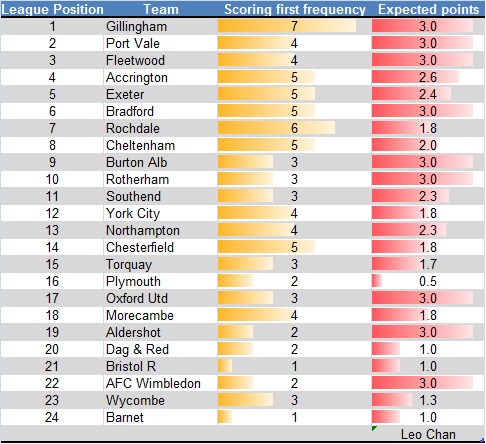

Team

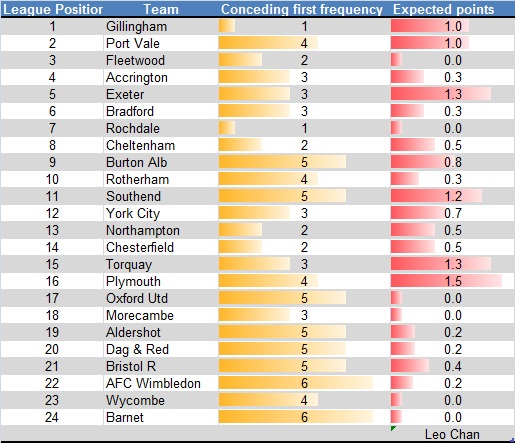

The tables are listed according to the league position (updated to 1/10). The above table is about scoring first. The first 8 teams in the league table all scored first goals for at least 4 times. Among these 8 teams, 4 of them get expected points of 3 which means that whey they scored first, they kept the winning position and won the game every time. Gillingham scored first goal in 7 out of 8 games which is a brilliant result. Moreover, they retained and won all those 7 games which make them the best in league 2. Rochdale performed very well since they scored first goal 6 times, which is the second best. However, their weakness is to retain the winning position because they can only get 1.8 expected points, which is the worst in the top half of the table. Plymouth scored first goal twice but they get only 0.5 expected points per game which means they couldn’t won a game even they scored first. This result is the worst in the league. We would look at the conceding first in the following table.

Although Plymouth is the worst team in retaining winning position, they are the strongest team in the league 2 to bounce back from conceding first. They conceded first goal four times, but they bounced back and won the game twice so they got 1.5 expected points per game, which is 50% better than a draw. This is the best result in the league 2. Exeter and Torquay are the second best teams, getting 1.3 expected points. It is worthy to note that Torquay and Plymouth are at the 15th and 16th of the table, but they are the two best team to bounce back from conceding first. This can explain why in the league position chart positions 13-18 performs surprisingly better than expected.

Conclusion:

- Scoring in 16-30, 31-45 minutes (30 minutes before half time) can get higher expected points

- Conceding 15 minutes before half time would be the worst time to concede the first goal

- Playing in home is more likely to retain the winning position

- In terms of bouncing back, there is no difference in playing home and away games

- The 12 teams in the top half of league table are much better in retaining winning position than the bottom half of the table. Among those 12 teams in the top half of table, the first 6 teams are significantly better than positions 7-12 teams.

- Positions 19-24 teams are obviously weak in bouncing back when conceding first

- Gillingham is the strongest team to score first and retain the winning position

- Rochdale is strong in scoring first but weak at retaining the winning position to the end of the game

- Plymouth is a special team. They are the worst team in scoring first and get only 0.5 expected points. However, they are the strongest team in bouncing back from conceding first, getting 1.5 expected points.

This is my first analysis article about league 2. I will write at least a few more articles about league 2 this season.

Motion Analysis in Football

Nowadays, many coaches start using notational analysis by pen and paper to help their coaching. For example, they count the number of passes, shots and crosses etc to see how the team performed and which area can be improved. Apart from notational analysis, the coaches can improve their coaching by knowing more about motion analysis in football as well. In my previous article (here), I discussed about what motion analysis is. In short, motion analysis is the process of classifying activities according to intensity of movements (Strudwick and Reilly 2001). The three elements that should be considered are intensity (or quality), duration (or distance) and frequency (Carling et al 2005). The activities were coded according to intensity of movement, e.g. walking, jogging, cruising and sprinting. By using the information, the coaches can design specific drills to fit the football players in different levels and positions in order to achieve higher efficiency of improving performance.

Work rate activity profiles

One of the early researches about motion analysis in football was from Reilly and Thomas (1976). They found that the overall distance covered by outfield player during a match consists of 24% walking, 36% jogging, 20% cruising, 11% sprinting, 7% moving backwards and 2% moving in possession of the ball. The below figure visualises the above finding.

Figure 1 Relative distances covered in different categories of activity for outfield players during soccer match-play

They found two things about the ratio of low-high intensity exercise. The ratio is 2.2 to 1 in terms of distance covered and 7 to 1 in terms of time. Different researchers have different activity profiles. For example, Bradley et al (2009) classified players’ activities into standing, walking, jogging, running, high-speed running and sprinting. Generally, the activities would be classified into two categories: low to moderate intensity activity and high intensity activity and different researches had similar results. Bradley et al (2009) found that low-intensity activity represented 85.4% of total time. Bloomfield et al (2007) had a similar finding that 80-90% of performance is spent in low to moderate intensity activity whereas the remaining 10-20% are high intensity activities. From the above figure, you may realize that only 2% of the total distance covered by top players is with the ball, that means vast majority of actions are “off the ball”, for instance, running into space, support teammates, tracking opposing players. If you are a coach, try to ask yourself “Should I put more effort and time coaching players without the ball rather than just coaching the player with the ball?”. Some other findings such as player has a short rest pause of only 3s every 2 minutes and players generally have to run with effort (cruise or sprint) every 30s (Reilly and Williams 2003) may be useful for the coaches as well.

For the mean distance covered, Strudwick and Reilly (2001) stated that the top division players in the 1970s covered a mean distance of 8680m. In contemporary premier league the figure became 11264m. They suggested that it was because there are more passes, runs with the ball, dribbles and crosses which lead to the increase in the tempo of games. In the research of Bradley et al (2009), the result is 10714m. If you are a coach of adult’s team, the information can be a benchmark for your reference about distance covered for your players.

Does work rate and movement vary by the different positional roles?

Some coaches may realize there should be some differences but they may not realize what the differences are. There are positional differences in work rate and fitness levels. In terms of distance covered, midfield players have the greatest distance covered which is reasonable because they acts as links between defence and attack (Reilly and Thomas 1976)(Ekblom 1986)(Bangsbo et al 1991). This finding was supported by other research. For example, midfielders were engaged in a significantly less amount of time standing still and shuffling and the most time running and sprinting (Bloomfield et al 2007). Greatest distance covered sprinting were found in strikers and midfield players (Reilly and Williams 2003). In terms of the difference between full backs and centre backs, full backs covered more overall distance than the centre backs, but less distance sprinting (Strudwick and Reilly 2001)(Reilly and Williams 2003).

Apart from work rate, motion analysis analyse movement as well. There are different movement characteristics for different positions. Here is the list of findings from different researchers.

Defenders:

- Perform the highest amount of jogging, skipping and shuffling movements and spend a significantly less amount of time sprinting and running than the other positions (Bloomfield et al 2007)

- More body strength in order to compete with the strikers

- Highest amount of backwards and lateral movements (Rienze et al 2000)

- More turns of 0-90 degree(Bloomfield et al 2007)

- Ability to move backwards and sideways is important for defenders (Carling et al 2005)

- To be heavier and with higher BMI, although only slightly taller, than midfielders (Bloomfield et al 2005)

Midfielders

- Were engaged in a significantly less amount of time standing still and shuffling and the most time running and sprinting (Bloomfield et al 2007)

- Perform the most directly forward movements (Rienze et al 2000)

- More diagonal and arc movements (Bloomfield et al 2007)

- More turns of 270-360 degree (Bloomfield et al 2007)

Strikers/Forwards:

- Perform the most of the other types movements (jumping, landing, diving, sliding slowing downing, falling and getting up)

- Perform the most physical contact at high intensity,

- More stopping, these activities produce shearing forces on the lower limbs and Besier et al (2001) suggested that strength training and prehabilitation practices must be adopted and emphasised.

- More diagonal and arc movements (Bloomfield et al 2007)

- More turns of 270-360 degree (Bloomfield et al 2007)

- Forwards tend to receive the ball when sprinting (Carling et al 2005)

- To be heavier and with higher BMI, although only slightly taller, than midfielders (Bloomfield et al 2005)

I hope these are useful for the coaches to know more about different requirements in different positions in terms of work rate, movement and even body strength.

Does work rate vary by the styles of play?

Although all the work rate research done by different researchers are facts, we should think about whether it is ‘all of the facts’. Are they always 100% right and can be applied to all situations? I think style of play is a factor which can affect the work rate of a team. Some researchers had the same view also (Bradley et al 2009)(Reilly and Williams 2003). In possession play, the pace of the game is slowed down, the attacking moves are delayed and the players will wait until opportunities rises. In direct play, the team tries to raise the pace of the game by passing the ball quickly in order to transfer the ball quickly from defence to attack to create opportunities. Therefore, the team would prefer long passes rather than a sequence of short passes. Apart from possession play and direct play which are the most discussed styles of play, we shouldn’t ignore Total football and South American style. I don’t know much about these two styles but I think the work rate requirement of Total football would be similar to direct play as they exchanges positions frequently. South American style is more rhythmic and the overall distance covered is 1.5km less than in the English Premier League (Rienze et al 2000).

Summary

In the 90-minute match time, 80-90% of performance is spent in low to moderate intensity activity whereas the remaining 10-20% are high intensity activities. However, we must remember that most of the key incidents of the game are happened within those 10-20% high intensity activities. There are significant differences existing between strikers, midfield players and defenders in terms of work rate, activity profiles and movements. For example, defenders have the most of backwards and lateral movements. Midfielders covered the greatest distance. Strikers/ forwards tend to receive the ball when sprinting. I hope this article would be useful for the coaches to know more about different requirements of different positions in order to design more specific conditioning programs for the players. Defenders and strikers need speed and agility type drills while midfielders need interval running over longer distances.

References

BANGSBO, J., L. NORREGAARD and F. THORSO, 1991. Activity profile of professional soccer. Canadian Journal of Sports Science, 16, 110-16

BESIER, T.F., D.G. LLOYD, J.L. COCHRANE and T.R. ACKLAND, 2001. External loading of the knee joint during running and cutting manoeuvres. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise, 33, 1168-1175

BLOOMFIELD, J., R.C.J. POLMAN, R. BUTTERLY and P.G. O’DONOGHUE, 2005. An analysis of quality and body composition of four European soccer leagues. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 45, 58-67

BLOOMFIELD, J., R. POLMAN and P. O’DONOGHUE, 2007. Physical demands of different positions in FA Premier League Soccer. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 6, 63-70

BRADLEY, P.S., W. SHELDON, B. WOOSTER, P.OLSEN, P.BOANAS and P. KRUSTRUP, 2009. High-intensity running in English FA Premier League soccer matches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(2), 159-168

CARLING, C. et al., 2005. Handbook of Soccer Match Analysis. Oxon: Routledge

EKBLOM, B., 1986. Applied physiology of soccer. Sports Medicine, 3, 50-60

REILLY, T. and A., M. WILLIAMS, 2003. Science and Soccer. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge

REILLY, T. and V. THOMAS, 1976. A motion analysis of work-rate in different positional roles in professional football match-play. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 2, 87-97

RIENZE, E., B. DRUST, T. REILLY, J.E.L. CARTER and A. MARTIN, 2000. Investigation of anthropometric and work-rate profiles of elite South American international players. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 40, 162-9

STRUDWICK, T. and T. REILLY, 2001. Work-rate Profiles of Elite Premier League Football Players. Journal of Exercise Science, 4(2)